点击查看第二章

点击查看第三章

国际市场营销学(英文版·原书第7版)

Global Marketing(7th Edition)

[丹] 斯文德·霍伦森(Svend Hollensen) 著

CHAPTER 1 Global marketing in the firm

1.1 Introduction to globalization

After two years (2008—10) in economic crisis mode, business executives are again looking to the future. As they are re-engaging in global marketing strategy thinking, many executives are wondering if the turmoil was merely another turn of the business cycle or a restructuring of the global economic order. However, although growth in the globalization of goods and services has stalled for a period, because international trade has dedined along with demand, the overall globalization trend is unlikely to reverse (Beinhocker et al., 2009).

In 2005 Thomas L. Friedman published his international best selling book The World is Flat (Fretdman, 2005). It analyses globalization, primarily in the early wenry-firsr century, and the picture has changed dramatically. The title is a metaphor for viewing the world as a level phying field in terms of commerce, where all play-ers and competitors have an equal opportunity. Companies from every part of the world will be competing with each other in every corner of rhe world markets — for customersv resources, talent and intellectual capital. Products and services will flow from many locations to many destinations. Friedman mentions that many companies in, for example, the Ukraine, India and China provide human-based subsupplies for multi nation al companies. In this way, these companies in emerging and developing countries are becoming integral parts of complex global supply chains for large mulrinarional companies, like Dell, SAP, IBM and Microsoft.

Pankaj Gheniawar has contradicted Friedman's view of the world being fhr (Ghemawar, 2008). In his latest book, Ghemawat introduces World 3.0, a world that is neither a set of distinct nation-states (VC^orld 1.0) nor the stateless ideal (World 2.0) that seems implicit in rhe The world is flaf strategies of so many companies. In such a World 3.0 (Ghemawat, 2011a), home matters, but so do countries abroad. Ghemawat argues that when distances (grographic, cukural, administrarive/political and economic) increase, cross-border trade rends to decrease (Ghemawat, 2011b). Gheniawar chinks that it is certainly possible ro have a global strategy and a global organization in such a world. But rhe global strategy must be based not on the elimination of differences and distances among people, cultures and places, bur on an understanding of them.

1.2 The process of developing the global marketing plan

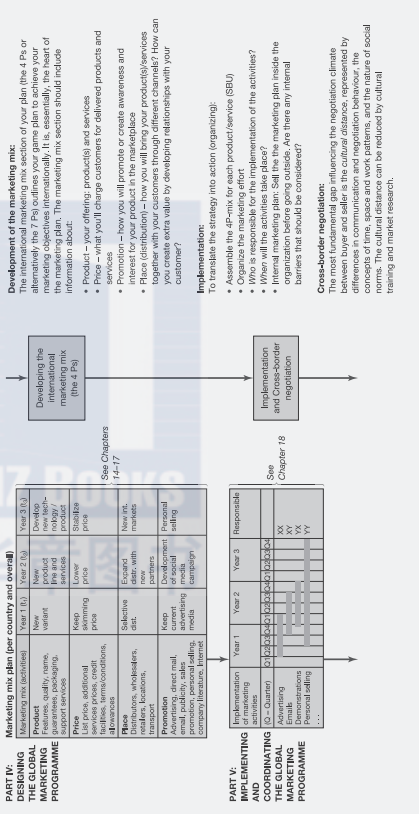

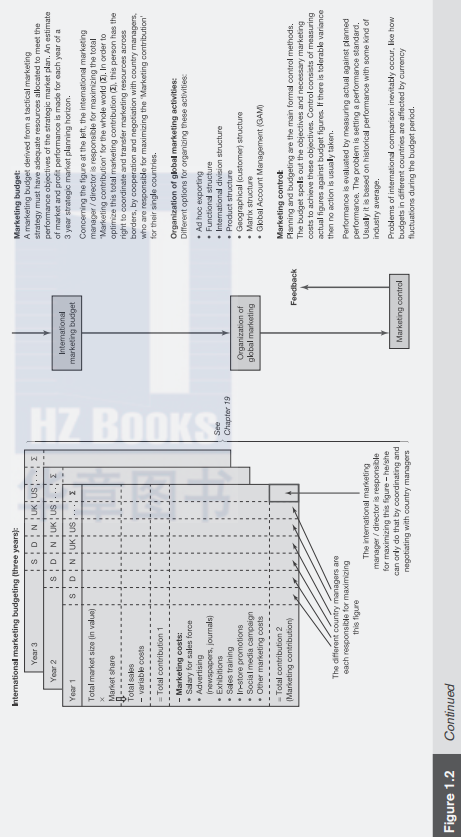

As the book has a dear decision-oriented approach, it is structured according to the five main decisions that marketing people in companies face in connection with the global marketing process. The 15 chapters are divided into five parts (Figure 1.1).

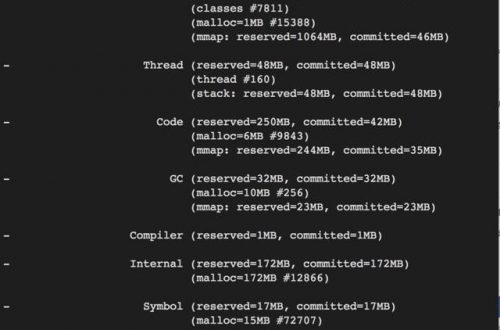

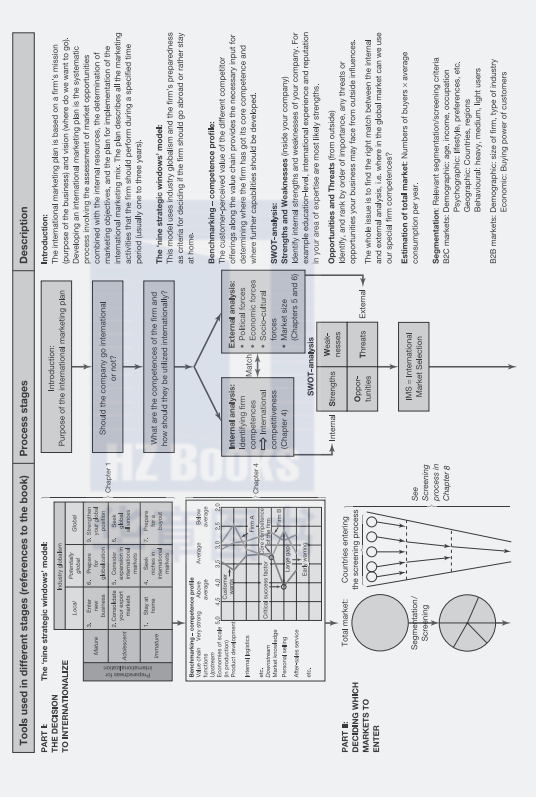

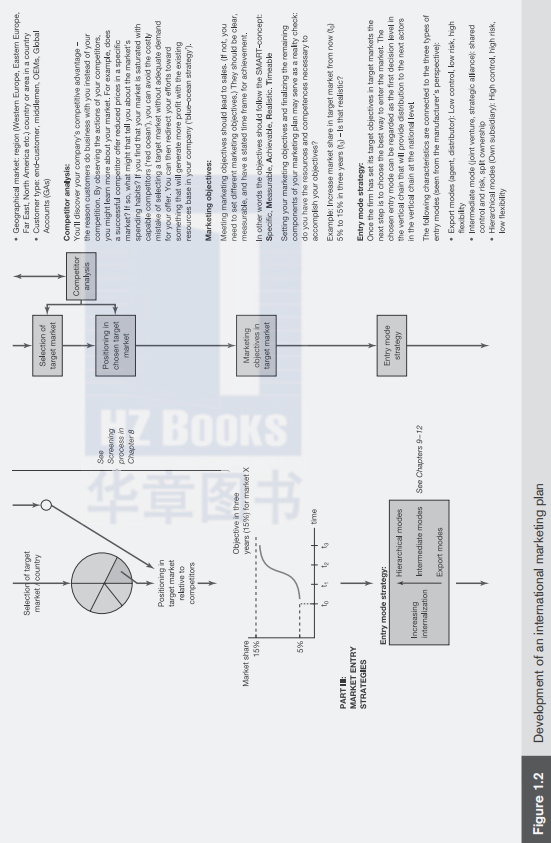

In the end. the firm's global competitiveness is mainly dependent on the end-result of the global marked ng stages: the global market big plan (see Figure 1.2). The purpose of rhe marketing plan is to create sustainable competitive advantages in the global marketplace. Generally, firms go th rough some kind of mental process in developing global marketing plans. In small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) this process is normally informal; in larger organizations it is often more systematized. Figure 1.2 offers a systematized approach to developing a global marketing phn — the sui皮s are illustrated using the most important models and concepts, which are explained and discussed throughout the chapters. Readers are advised to return to this figure throughout the book.

1.3 Comparison of the global marketing and management style of SMEs and LSEs

The reason underlying this Convergence' is that many large mukinationals (such as IBM, Philips, GM and ABB) have begun downsizing operations, so in reality many LSEs act like a confederation of small, autonomous, entrepreneurial and action-oriented companies. One can always question the change in orienrarion of SMEs. Some studies (e.g. Bonaccorsi, 1992) have rejecced rhe widely accepted proposition that firm size is positively related ro export intensity・ Furthermore, many researchers (e.g. Julien et u/., 1997) have found that SMEs as exporters do nor behave as a homogeneous group.

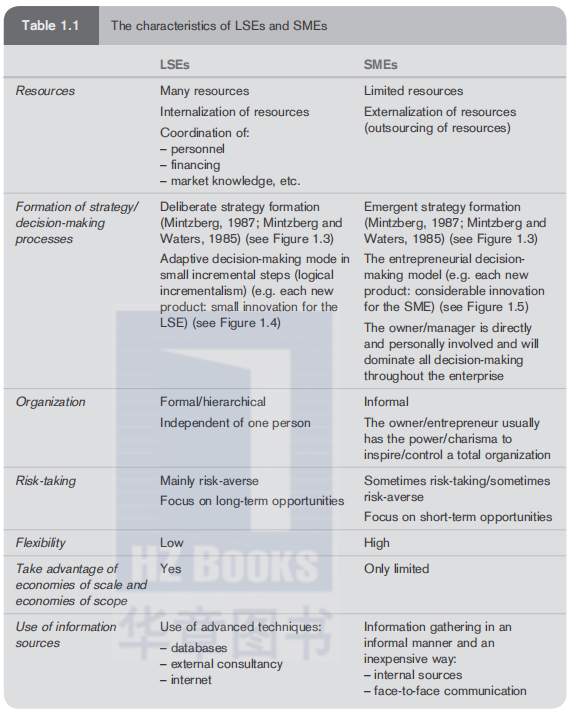

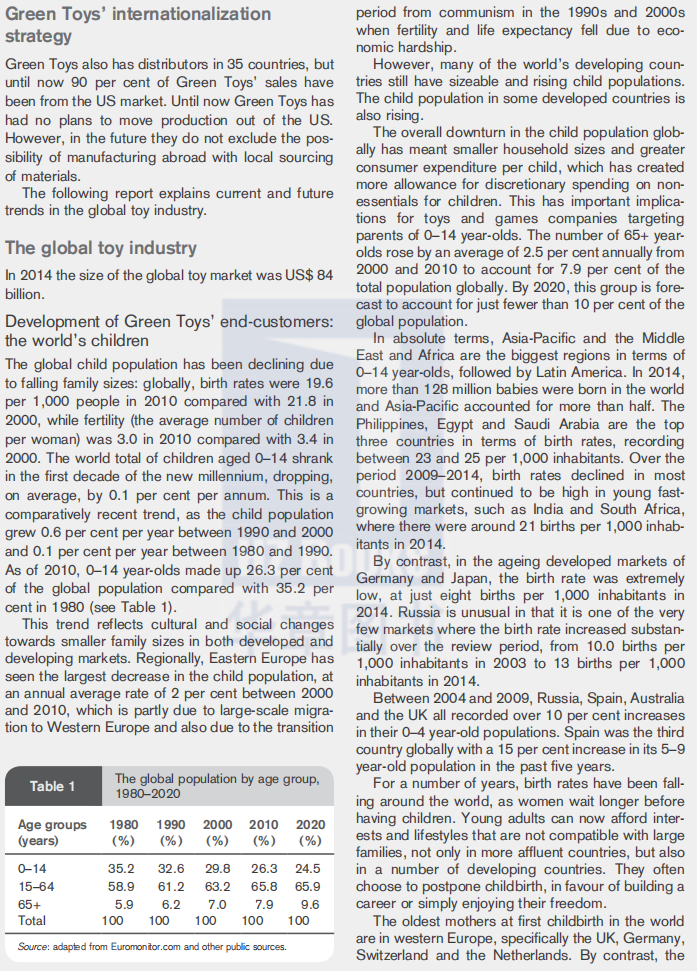

Table 1.1 gives an overview of the main qualirarive differences between management and marketing styles in SMEs and LSEs. We will discuss each of the headings in turn.

Resources

- FinanciaL A well-documented characteristic of SMEs is the lack of financial resources due ro a limited equity base. The owners put only a limited amount of capital into the business, which quickly becomes exhauseed.

- Business cducalion!specialist expertise. In contrast ro LSEs, a charaaerisric of SME managers is rheir limited formal business education. Traditionallyt the SME owner/ manager is a technical or craft expert and is unlikely to be trained in any of the major business disciplines. Therefore specialist expertise is often a constraint because managers in small businesses tend to be generalists rather than specialists. In addition, global marketing expertise is often rhe last of rhe business disciplines co be acquired by an expanding SME; finance and production experts usually precede the acquisition of a marketing counterpart. Therefore it is nor unusual ro see owners of SMEs closely involved in sales, distribution, price setting and, especially, product development.

Formation of strategy/decision-making processes

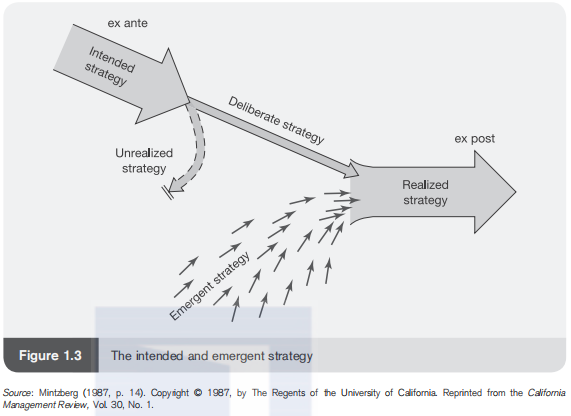

As is seen in Figure 1.3. rhe realized strategy (rhe observable output of an organization's activity) is a result of the mix between the intended f planned') strategy and the emergent ("not planned') strategy. No companies form a purely deliberate or intended strategy. In practice, all enterprises will have some elements of both intended and emergent strategy.

In the case of the deliberate (planned) strategy (mainly LSEs), managers try to formulate their intentions as precisely as possible and then strive to implement these wirh a minimum of distortion.

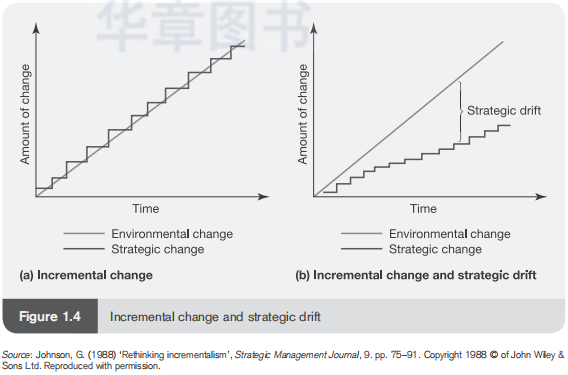

This planning approach Assumes a progressive series, of steps of goal setting, analysis, evaluation^ selection and planning of implementation to achieve an optimal long-term direction for the organization, Qohnson, 1988). Another approach for the process of strategic nunagenwnt is so-called logical(Quinn, 1980), where continual adjustments in straiegy proceed flexibly and experimentally. If such small movements in strategy prove successful then further devdopment of the strategy can take place. According ro Johnson (1988) managers may well see themselves as managing incrementally, but this does not mean that they succeed in keeping pace with environmental change. Somerimes the incrementally adjustol strategic changesand rhe environmental market changes move apart and a stnitegic drift arises (see Figure 1.4).

Exhibit 1.1 gives an example of strategic drift.

On the other hand, the SME is characterized by the entrepreneurial decision-making model (Figure 1.5). Here more drastic changes in strategy are possible because decisionmaking is intuitive, loose and unstructured. In Figure IS the range of possible realized strategies is determined by an interval of possible outcomes. SME entrepreneurs are noted for their propensiry to seek new opportunities, and this natural propensity for change, inherent in entrepreneurs, can lead to considerable changes in the enterprise's growth direction. Because the entrepreneur changes focus, this growth is not planned or coordinated and can therefore be characterized by sporadic decisions that have an impact on the overall direction in which the enterprise is going.

Organization

Compared with LSEs, the employees in SMEs are usually closer ro the enrreprencur and, because of rhe entrepreneur's influence, these employees muse conform to his or her personality and sryle if they are to remain employees.

Risk-taking

There are, of course, different degrees of risk. Normally the LSEs will be risk-averse because of rheir use of a decision-making model that emphasizes small incremental steps with a focus on long-term opportunities.

In SMEs, risk-raking depends on rhe circumstances. It can occur in situations where rhe survival of rhe enterprise may be under threat, or where a major competitor is undermining rhe activities of the enterprise. Entrepreneurs may also be taking risks when they have not gathered al! the relevant information, and thus may have ignored some imponanr facts in the decision-making process.

On the other hand, there are, of course, some circumstances in which an SME will be risk-averse. This often occurs when an enterprise has been damaged by previous risk- taking and the entrepreneur is reluctant ro take any kind of risk until confidence returns.

Flexibility

Because of rhe shorter communication lines between the enterprise and its customers, SMEs can react in a quicker and more flexible way to customer enquiries.

Economies of scale and economies of scope

Economies of scale

Accumulated volume in production and sales will result in lower cost price per unit due ro * experience curve effects' and increased efficiency in production, marketing, etc. Building a global presence automatically expands a firm's scale of operations, giving it larger production capacity and a larger asset base. However, larger scale will create a competitive advantage only if the company systems tic Ally converts wale into economies of scale.

In principle, the benefits of economies of scale can appear in different ways (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2001):

- Reducing operating coses per unit and spreading fixed costs over a larger volume due to experience curve effects.

- Pooling global p urc ha sin g gives rhe opportunity ro concentrate global purchasing power over suppliers. This generally leads co volume discounts and lower transaction costs.

- A larger scale gives rhe global player rhe opportunity to build centres of excellence for rhe development of specific technologies or products. In order to do this, a company needs to focus a critical mass of talent in one location.

Because of size (bigger market share) and accumulaced experience, the LSEs will normally take advantage of these factors (see Exhibit 12 about Nintendo's Game Boy). SMEs rend to concentrate on lucrative, small, market segments. Such market segments are often too insignificanr for LSEs to bur can be subsc anti al and viable in respect of the SME. However, they will only result in a very limited market share of a given indusrry.

Economies of scope

Synergy effects and global scope can occur when rhe firm is serving several international markers: global scope is not taking place if an international marketer is serving a customer that operates in just one country. The customer should purchase a bundle of identical products and services across a number of countries. This global customer could source these products and services either from a horde of local suppliers or from a single global supplier (international marketer) that is present in all of irs markets. Compared with a horde of local suppliers, a single global supplier (marketer) can provide value for the global customer through greater consistency in the quality and features of products and services across countries, faster and smoother coord in at ion across countries and lower transaction costs.

The challenge in capmring rhe economies of scope at a global level lies in being responsive to the tension between two conflicting needs: the need for central coordination of most marketing mix elemencs, and the need for local autonomy in the aaual delivery of products and services (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2001).

The LSEs often serve many different markets (countries) on more continents and are thereby able to transfer experience acquired in one country ro another. Typically, SMEs serve only a very limited number of international markets outside their home marker. Sometimes the SME can make use of economies of scope when ir enters into an alliance or a joint venture with a partner who has what the particular SME is missing in the international marker in question: a complementary product programme or local market knowledge.

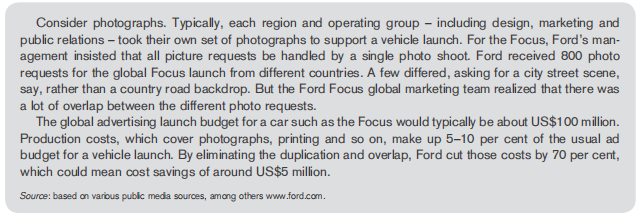

Another example of economies of scale and scope can be found in rhe world car industry. Most car companies use similar engines and gearboxes across their entire product range so that rhe same engines or gearboxes can be installed in different models of cars. This generates enormous potential cost savings for companies such as Ford or Volkswagen. It provides both economies of scale (decreased cost per unit of output), by producing a larger absolute volume of engines or gearboxes, and economies of scope (reusing a resource from one business/counrry in addirional bus.inesses/counrries). Ir is not surprising that rhe car industry has experienced a wave of mergers and acqu is it io ns aimed at creating larger global car companies of sufficient size ro benefit from these factors.

Use of information sources

Typically, LSEs rely on commissioned market reports produced by reputable (and well- paid!) international consultancy firms as their source of viral global markering information. SMEs usually gather informarion in an informal manner through the use of face-to-face communication. The entrepreneur is able to synthesize this informarion unconsciously and use it to make decisions. The acquired information is mostly incomplete and fragmented, and evaluations are based on. intuition and often guesswork. The whole process, is dominated by rhe desire to find a circumstance that is ripe for exploitation.

Furthermore, rhe demand for complex information grows as the SME selects a more and more explicit orientation towards rhe international market and as the firm evolves from a production-oriented ‘upstream’) to a more markering-oriented ('downstream') firm (Cafferata and Mensi, 1995).

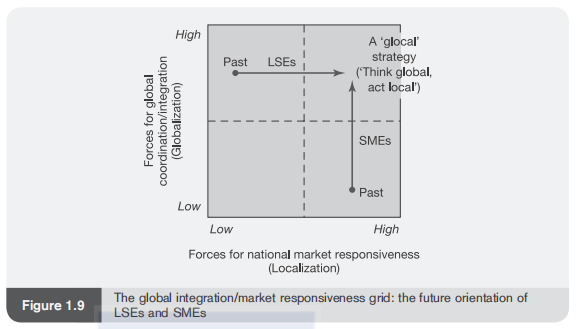

As a reaction ro pressures from international markets, both LSEs and SMEs evolve towards a globally integrated bur marker-responsive strategy. However, rhe starting points of the two firm types are different (see Figure 1.3). The huge global companies have traditionally based their strategy on taking advantage of economies of scale by launching standardized products on a worldwide basis. These companies have realized that a higher degree of market responsiveness is necessary ro main rain competitiveness in national markets. On the other hand, SMEs have traditionally regarded national markets as independent of each other. However, as internarional competences have evolved, they have begun co realize that there is interconnectedness between cheir different international markets. They now recogn ize rhe benefits of coordinating the different nacional marketing st rar e- gies in order ro utilize economies of scale in research and development (R& D), production and marketing.

Exhibit 1.3 shows that LSEs (illustrated here by the recent Ford Focus case) still try ro focus on 'economies of scale' by reducing rhe number of variations among cars in different countries fOne Ford').

1.4 Should the company internationalize at all?

In the face of globalization and an increasingly interconnected world, many firms attempt to expand their sales into foreign markets. International expansion provides new and potentially more profitable markets, helps to increase rhe firm's competitiveness, and facilities access to new product ideas, manufacturing innovations and rhe latest technology. However, internationalization is unlikely to be successful unless the firm prepares in advance. Advance planning has often been regarded as important co rhe success of new inter national ventures (Kn ighr, 2000).

Solberg (1997) discusses rhe conditions under which the company should 'stay ar home' or further 'strengthen rhe global position' as two extremes (see Figure 1.6). The frame-work in Figure 13 is based on rhe dimensions industnr globalism and preparedness for internarionalization.

Industry globalism

In principle, the firm cannot influence the degree of industry globalism, as it is mainly determined by rhe international marketing environment Here the strategic behaviour of firms depends on rhe international comperirive structure within an industry. In the case of a high degree of industry globalism there are many interdependencies between markers, customers and suppliers, and the industry is dominured by a tew large, powerful players (global), whereas the other end (local) represents a multidomestic market environment, where markets exist independently of one another. Examples of very global industries are those making PCs, IT (software), CDs, films and aircraft (the two dominant players being Boeing and Airbus). Examples of more local industries are those that are more culture-bounded, such as hairdressing, foods and dairies (e.g. brown cheese in Norway).

Preparedness for internationalization

This dimension is mainly determined by the firm. The degree of preparedness is dependent on the firm's ability to carry our strategies in the international marketplace, i.e. the actual skills in inrernarional business operations. These skills or organizational capabilities may consist of personal characteristics (e.g. language, cultural sensitivity), managers' international experience or financial resources. The well-prepared company (mature) has a good basis for dominating the international markets and consequently it would gain higher market share.

In the global/international marketing literature the 'Staying at home' alternative is nor discussed thoroughly. However, Solberg (1997) argues that with limited international experience and a weak posirion in the home marker there is little reason for a firm to engage in inrernational markets. Instead the firm should try to improve its performance in its home market. This akernarive is window number 1 in Figure 1.6.

If the firm finds itself in a global industry as a dwarf among large multinational firms, Solberg (1997) argues that ic may seek ways to increase its net worth so as to attract partners for a future buyout bid. This alternative (window number 7 in Figure 1.6) may be relevant to SMEs selling advanced high-tech components (as subsuppliers) to large industrial companies with a global nerwork. In sicuarions with fluauarions in rhe global demand, the SME (with limited financial resources) will ofren be financially vulnerable. If rhe firm has already acquired some competence in international business operations, it can overcome some of its competitive disadvantage by going into alliances with firms that have complementary competences (window number 8). The other windows in Figure 1.6 are further discussed by Solberg (1997).

1.5 Development of the 'global marketing' concept

Basically4global marketing' consists of finding and satisfying global customer needs better than the competition, and coordinaring marketing activities within rhe constraints of rhe global environment. The nature of the firm's response co global market opportunicies depends greatly on the managerment's assumptions or beliefs, both conscious and unconscious, about doing business around the world. This world view of a firm's business activities can be described according to the EPRG framework (Perlmutter, 1969; Chakravarthy and Perlmutrer, 1985), the four orientations of which are summarized as follows:

1.Ethnocentric: the home country is superior and the needs of rhe home country are most relevant. Essentially the heidquirrers extends its ways of doing business to its foreign affiliates. Controls are highly centralized and the organization and technology implemented in foreign locations will be hrgdy rhe same as in the home country.

2.Polycentric (mukidomesric): each country is unique and should therefore be targeted in a different way. The polycentric enterprise recognizes that there are different conditions for producrion and marketing in different locations and tries to adapt to those different conditions in order to maximize profits in each location. The control is highly decentralized among affiliates, and communication between headquarters and affiliates is limited.

3.Regio centric:: the world consists of regions (e.g. Europe, Asia, the Middle East). The firm tries co integrate and coordinate its marketing programme within regions, but not across them.

4.Geocentric (global): the world is getting smaller and smaller. The firm may offer global product concepts bur with local adaptation fthink global, act local').

The regjo- and geocentric firm (in contrast to the ethnocentric and polycentric) seeks to organize and integrate producrion and marketing on a regional or global scale. Each international unit is an essential part of the overall multi national network, and communications and controls between headquarters and affiliates are less top-down than in the case of the ethnocentric firm.

Many international markers are converging, as communication and logistic networks are integrated on a global scale. Ac rhe same rime, other international markets are becoming more diverse as company managers are encountering economic and cultural heterogeneity. This means chat firms need to balance tensions in adapting to different demands from customers in divergent markets, which require different skills and resources while attempting to transfer knowledge and learning between rhe established markets and these new markers (Douglas and Craig, 2011).

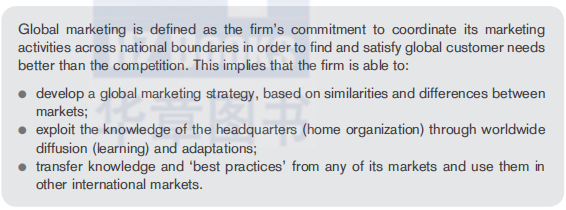

This leads us ro a definition of global marketing:

There follows an explanation of some key terms:

- Coordinate its marketing activities: coordinating and integrating marketing strategies and implementing them across global markets, which involves centralization, delegation, standardization and local responsiveness.

- Find global customer needs: this involves carrying out international marketing research and analysing marker segments, as well as seeking to understand similarities and differences in customer groups across countries.

- Satisfy global customers: adapting products, services and elements of the marketing mix to satisfy different customer needs across countries and regions.

- Being better than the competition: assessing, monitoring and responding to global competition by offering better value, lower prices, higher quality, superior distribution, great advertising strategies or superior brand image.

The second part of rhe global marketing definition is also illustrated in Figure 1.7 and further commented on in the followings.

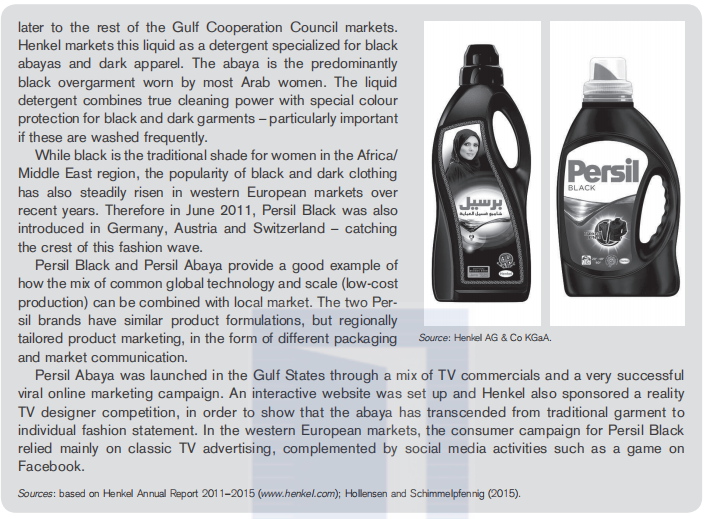

This global marketing strategy strives to achieve the slogan think globally bur act locally' (the so-called 'glocallzation' framework) through dynamic interdependence between headquarters and subsidiaries. Organizations following such a strategy coordinate rheir efforts, ensur ing local flexibility while exploiting the benefits of global integration and efficiencies, as well as ensuring worldwide diffusion of innovation (see Exhibit 1.5).

Principally, the value chain function should be carried our where there is the highest competence (and the greatest cosr-effecriveness), and this is not necessarily at head office (Bellin and Pham, 2007).

The two extremes in global marketing, globalization and localization, can be combined into the "glocalizarion* framework, as shown in Figure 1.7.

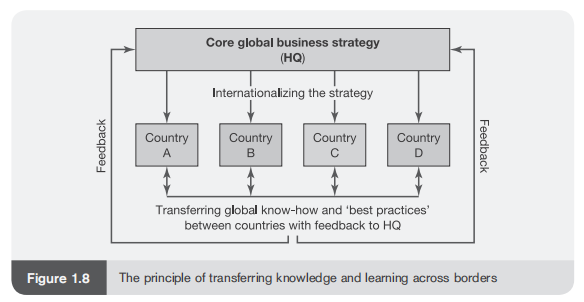

A key element in knowledge management is the continuous learning from experiences. In practical terms, the aim of knowledge management as a Iearning-fbcused activity across borders is to keep track of valuable capabilities used in one market that could be used elsewhere (in other ^ographic markets), so that firms can continually update their knowledge. This is also illustrated in Figure 1.8 with rhe transfer of knowledge and 4best prac- rices' from market to market. However, knowledge developed and used in one cultural context is not always easily transferred to another. The lack of personal relationships, the absence of trust and "cultural distance' all conspire to create resistance, fricrions and misunderstandings in cross-cultural knowledge management.

With globalization becoming a centrepiece in rhe business strategy of many firms 一 be they engaged in product development or providing services — rhe ability ro manage the "global knowledge engine' to achieve a competitive edge in today's knowledge-intensive economy is one of rhe keys to sustainable competitiveness. However, in the context of global marketing the management of knowledge sde facto a cross-cultural activity, whose key task is to foster and continually up grad e col la bora ci ve cross-cultural learning (this will be further discussed in Chapter 14). Of course, the kind and/or type of knowledge that is strategic for an organization and which needs to be manned for competitiveness varies depending on the business context and rhe value of different types of knowledge associated with it.

1.6 Forces for global integration and market responsiveness

In Figure 1.9 ir is assumed that SMEs and LSEs are learning from each other. The consequence of both movements may be an aaion-oriented approach, where firms use the strengths of both orientations. The following section will discuss the differences in the starting points of LSEs and SMEs in Figure 1.9. The result of rhe convergence movement of LSEs and SMEs into rhe upper-right corner can be illustrated by Figiire 1.9.

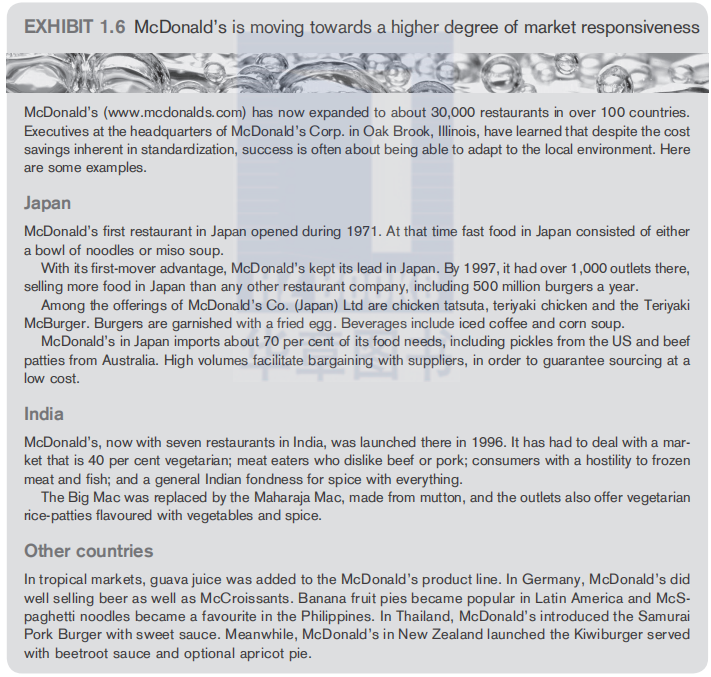

An example of a LSE's movement from ’left' to Pighr' is given in Exhibit 1.6, where McDonald's has adapted irs menus to rhe local food cultures. SMEs been strong on 'high degree of responsiveness', bur their tendency to decaitralization and local decision-making has made them more vulnerable to a low degree of coordination across borders (which, by contrast, is rhe strength of LSEs).

The terms "glocal strategy' and iglocalizarion, have been introduced to reflect and combine the two dimensions in Figure 1.9: globalization (y'axis) and localization (x'axis). The glocal strategy approach reflects rhe aspirations of a global integrated strategy, while recogn izing rhe importance of local ada prat ion s/ ma rket responsiveness. In this way, giocalizarion tries to oprimize the balance becween standardization and adaptation of the firm's international marketing activities (Svensson, 2001, 2002; Bailey el u/.,20I5).

First let us try to explain rhe underlying forces for global coordination/global integration and market responsiveness in Figure 1.9.

Forces for 'global coordination/integration'

In the shift towards integrated global marketing, greater importance will be attached ro rransnational similarities for target markers across national borders and less on crossnational differences. The major drivers tor this shift are as follows (Sheth and Parvariyar, 2001; Segal-Horn, 2002):

- Reftiotuil of trade harriers (dereguLitio/t). Removal of historic barriers, both tariff (such as import raxes) and non-rariff (such as safety regulations), which have constituted barriers to trade across national boundaries. Deregularion has occurred at all levels: narional, regional (within national trading blocs) and internacional. Thus deregulation has an impact on globalizarion, as ir reduces the ti me, costs and complexity involved in trading across boundaries.

- Global acconttsl customers. As customers become global and rationalize their procurement activities, they demand rhar suppliers provide them with global services to meet their unique global needs. Often this may consist of global delivery of products, assured supply and service systems, uniform characteristics and global pricing. Several LSEs, such as IBM, Boeing, IKEA, Siemens and ABB, make such 'global' demands on rheir smaller suppliers, typical SMEs. For rhef^e SMEs, managing such global accounts requires cross-functional customer teams, in order to deploy quality consistency across all functional units.

- Relationship mandgonent!netivork organization. As we move towards global markets ir is becoming increasingly necessary to rely on a network of relationships with external organizations, for example, customer and supplier relationships to pre-enipt competition. Firms may also have to work with internal units (e.g. sales subsidiaries) located in many and various parts of the world. Business alliances and network relationships help to reduce market uncertainries, particularly in the context of rapidly converging technologies and the need for higher amounts of resources to cover global markets. However, networked organizations need more coordination and communication.

- Standardized uwlduide technology. Earlier differences in world market demand were due ro rhe fact chat advanced technological products were primarily developed for rhe defence and government sectors before being scaled down for consumer applications. However, today rhe desire for gaining scale and scope in production is so high rhar worldwide availability of products and services should escalate. As a consequence we may wimess more homogeneity in the demand and usage of consumer electronics across nations. Today 'phig-and・phy' modules are combined co create produces very similar across markets. Examples of chat are smartphones, that can be produced ar gcxxl quality, nor only by Apple and Samsung, bur also by a Chinese manufacturer, like Xiaomi, which in 2014 captured no. 1 position in rhe Chinese smartphone market, and is now expandingro other international markets (Santos and Williamson, 2015).

- Worldicide markets. The concept of diffusions of innovarions, from rhe home country ro rhe rest of the world rends co be replaced by che concept of worldwide markets. Worldwide markets are likdy ro develop because they can rely on world demographics. For example, if a marketer targets its products or services to the teenagers of rhe world, it is relatively easy ro develop a worldwide strategy for that segment and draw up operational plans to provide target marker coverage on a global basis. This is becoming increasingly evident in soft drinks, clothing and sports shoes, especially in the internet economy.

- 'Global village'. The term "global village* refers co the phenomenon in which rhe world's population shares commonly recognized cultural symbols. The business consequence of this is rhat similar products and services can be sold ro similar groups of customers in almost any country in rhe world. Cultural homogenization therefore implies the potential for the worldwide convergence of markets and the emergence of a global marketplace, in which brands such as Coke, Nike and Levi's are universally desired.

- Worldivide com mu nicat io h. New inrerner-based 'low-cost' communicacion methods (e.g. e-mailing, e-commerce) ease commonicarion and trade across different parrs of the world. As a result, aiscomers within narional markers are able ro buy similar pnxlucrs and similar services across parts of the world.

- Global cost drivers. These are categorized as "economies of scale' and 'economies of scope'. In the drive to reduce costs, many established mukinacionak have focused increasingly on activities with che highest returns. This means char lower-value activities are outsourced toemerging and developing countries with lower hhour costs. The result is that once-closed value chains have been opened up, enabling local players to source 4plug-aiid-play' modular designs to big mukiiiarionals, or even to develop local brands themsel ves (Santos and Williamson, 2015).

Forces for 'market responsiveness'

These are as follows:

- Cultural differences. Despite the advent of rhe "global village', cultural diversity clearly cont in ues co exist. Cu Itural differences often pose major difficulties in international negoriations and marketing management. These cultural differences ref leer differences in personal values and in the assumptions people make about how business is organized. Every culture has its opposing values. Markets are people, not products. There may be global products, but there are nor global people.

- Regiondlism/protectionism. Regionalism is the grouping of countries into regional clusters based on geographic proximity. These clusters (such as the European Union or the North American Free Trade Agreement) have formed regional trading blocs, which may represent a significant barrier to globalization, since regional era de is often seen as incomparible with global trade. In this case, trade barriers that are removed from individual countries are simply reproduced for a region. and a set of countries. Thus all trading blocs create outsiders as well as insiders. Therefbre one may argue that regionalism results in a simation where protectionism reappears around regions rather than individual countries.

- Deglobalization trend. More than 2,500 years ago the Greek historian Herodotus (based on observations) claimed that everyone believes their native customs and religion are the best. Current movements in Arab countries, rhe big demonstrations accompanying conferences such as the World Economic Forum in Davos or rhe World Trade Organization (WTO) meetings show char there could be a return co old values, promoting barriers co rhe further success of globalization. Rhetorical words such as 'McDonald iza- tion', and 'Coca-Colonizarion', describe in a simple way fears of US cultural imperialism.

Exhibit 2.4 presents an example of British Telecommunications' experience with de-incernationalization of their American and Asian strategy (Turner and Gardiner, 2007).

1.7 The value chain as a framework for identifying international competitive advantage

The concept of the value chain

The value chain shown in Figure 1.10 provides a systematic means of displaying and categorizing acriviries. The activities performed by a firm in any industry can be grouped inro rhe nine generic categories shown.

At each stage of the value chain there exists an oppo rtunity to conrribure positively to rhe firm's compelirive strategy by performing some activity or process in a way that is better than and/or different from rhe competitors' offer, and so provide some uniqueness or advantage. If a firm attains such a competitive advantage, which is sustainable, defensible, profitable and valued by rhe market, then it may earn high rates of return, even though the industry structure may be unfavourable and rhe average profitability of the industry modest.

In competitive terms, value is the amount that buyers are willing ro pay for whac a firm provides chem with (perceived value). The value chain includes both cost and value drivers. Drivers are the underlying structural factors that explain why the cosr/value generated by a firm's acriviries differs from that of its rivals. Basically, a firm is profitabk if rhe value it commands exceeds the costs involved in creating rhe product. Creating value for buyers that exceeds the cost of doing so is rhe goal of any generic strategy. Sometimes value, inscead of cost, must be used in analysing competitive posirion, since firms often deliberately raise their costs in order to command a premium price via differentiation. The concept of buyers' perceived value will be discussed further in Section 4.4.

Before going into rhe details of rhe various value chain activities, it is important to realize that rhe firm's value chain is embedded in a larger stream of network acriviries in the total supply chain. Suppliers, rhe firm itself and business customers all have their oivn value chain, starring from the basic raw materials and going right chrough to those engaged in rhe delivery of the final product and service to the final customer.

The Porter concept of the value chain

Porter's (1986) original value chain displays total value and consists of value activities and margin. Value activities are the physically and technologically distinct accivities that a firm performs. These are the building blocks with which a firm creates a product valuabk ro its buyers. Ma rgin is rhe difference between total value (price) and rhe collective cost of performing the value activities.

Comperirive advantage is a function of either providing comparable buyer value more efficiently than competitors (lower cost), or performing activities ar comparable cost but in unique ways, that create more customer value than the competitors are able to offer and, hence, command a premium price (differenriarion). The firm might be able to identify elements of rhe value chain that are not worth the coses. These can then be unbundled and produced outside the firm (outsourced) ar a lower price.

Value activities can be divided into two broad types, primary activities and suppon activities. Primary activities, listed along the bottom of Figure LIO, are rhe acriviries involved in the physical creation of the product, its s-ale and transfer to the buyer, as well as after-sales assistance. In any firm, primary acriviries can be divided into the five generic categories shown in the figure. Support activities support the primary activities and each other by providing purchased inputs, technology, human resources and various firm-wide functions. The dotted lines reflect the fact that procurement, technology development and human resource management can be associated with specific primary activities as well as supporting the entire chain. Firm infrastructure is nor associated with particular primary acriviries, but supports rhe entire chain.

Primary activities

The primary acriviries of rhe organization are grouped into five main areas, as follows:

- bibound logistics. The acriviries concerned with receiving, scoring and distributing the inputs to rhe product/service. These include materials, handling, stock control and transport.

- Operations. The transformation of these various inputs into rhe final producr or service, e.g. machining, packaging, assembly, testing.

- Outbound logistics. The collection, storage and distribution of rhe product to customers. For tangible products this would involve warehousing, material handling and transport; in rhe case of services it may be more concerned with arrangements for bringing customers to rhe service if it is in a fixed location (e.g. sports events).

- Marketing and sales. These provide rhe means whereby consumers!users are made aware of rhe producc/service and are able to purchase it. This would include sales adminiscrarion, advertising and selling. In public services, communication networks that help users access a particular service are often important.

- Service. These are all the activities that enhance or maintain rhe value of a product/ service. Asugman et nL (1997) have defined after-sales service as "those acriviries in which a firm engages after purchase of irs product chat minimize porential problems related to product use, and maximize the value of rhe consumption experience'. After-sales service consists of the following: the installation and start-up of the purchased producr, rhe provision of spare parrs for products, the provision of repair services, technical advice regarding rhe product, and the provision and support of warranties.

Each of these groups of primary acriviries is linked to support activities.

Support activities

These can be divided into four areas:

- Proairement. This refers to the process of acquiring the various resource inputs co the primary activities (not to the resources themselves). As such, it occurs in many parts of the organization.

- Technology devdopment. All value activities have a 'technology', even if it is simply 'know-how' The key technologies may be concerned directly with the product (e.g. R&D, product design), with processes (e.g. process development) or with a particular resource (e.g. raw material improvements).

- Human resource ntanagetnent. This is a particularly important area that transcends all primary acriviries. It is concerned with rhe activities involved in recruiting, training, developing and rewarding people within the organization.

-

- The systems of planning, finance, quality control, ere. are crucially imp orca nr ro an organization's strategic capability in all primary activities. Infraseruc-ture also consists ot the structures and routines of the organization thar sustain its culture.

As indicated in Figure 1.10, a distinction is also made between the prcxluction-orienred, upsrream, activities and the more marketing-oriented, 'downstream' activities.

Figure 1.11 shows a simplified version of rhe value chain in Figure 1.10. This simplified version, characterized by the fact that it contains only the primary activities of rhe firm, will be used in most parts of this book.

Although value activities are the building blocks of competitive advantage, the value chain is not a collection of independent activities, but a system of interdependent activities. Value activity is related by horizontal linkages within the value chain. Linkages are reh- rionships between the way in which one value activity is dependent on the performance of another.

Furthermore, rhe chronological order of the activities in the value chain is not always as illustrated in Figure 1.11. In companies where orders are placed before production of the final product (build-to-order), the sales and marketing function takes place before production.

In understanding the competitive advantage of an organization, rhe strategic importance of the following types of linkage should be analysed in order to assess how they contribute ro cost reduction or value added. There are two kinds of linkage:

- btterfkil Ibtlzjges between activities within the same value chain, but perhaps on different planning levds within the firm;

- extent al Imk^iges between different value chains 'owned' by the different actors in rhe coral value system.

Internal linkages

There may be important links between the primary activities. In particular, choices will have been made about these relationships and how they influence value creauon and strategic capability. For example, a decision ro hold high levels of finished stock might ease prcxluciion scheduling problems and provide a faster response rime to the customer. However, it will probably add to rhe overall cost of operations. An assessment needs ro be made of whether rhe added value of 'stocking' is greater than the added cost. Suboptimization of the single value chain activities should be avoided. It iseasy ro miss this point in an analysis if, for example, the marketing activities and operations are assessed separately. The operations may look good because they are geared ro high-volume, low-variety, low-unit-cosr production. However, at the same time rhe marketing team may be selling quickness, flexibility and variety to the customers. When pur together these two potential strengths are weaknesses because they are nor in harmony, which is what a value chain requires. The link between a primary activity and a support activity may be rhe basis of competirive advantage. For example, an organization may have a unique system for procuring marerials. Many internarional hotels and travel companies use their computer systems to provide immediate 4real time' quotations and bookings worldwide from local access points.

As a supplement to comments about rhe linkages between the different activines, ir is also rdevanr to regard the value chain (illustrated in Figure 1.11 in a simplified form) as a rhorough-going model on all three planning levels in the organization.

In purely conceptual terms, a firm can be described as a pyramid as illustrated in Figure 1.12. It consists of an intricate conglomeration of decision and activity levels, having three disdner levels, but the main value chain activities are connected co all three strategic levds in the firm:

- The strategic level is responsible for formulation of the firm's mission statement, determining objectives, identifying the resources that will be required if rhe firm is to attain its objectives, and selecting rhe most appropriate corporate strategy for the firm co pursue.

- The nkutagerial leuel has the task of translating corporate objectives into functional and/or unit objectives and ensuring that resources placed at its disposal (e.g. in the marketing department) are used effectively in the pursuit of those activities chat will make the achievement of the firm's goals possible.

- The operational level is responsible for the effective performance of the tasks that underlie the achievement of unit/functional objectives. The achievement of operanonal objectives is what enables the firm to achieve its mana辟rial and strategic aims. All three levels are interdependent, and chriry of purpose from the top enables everybody in the firm to work in an integrated fashion towards a common aim.

External linkages

One of the key features of most industries is rhar a single organization rarely undertakes all value activities from produa design to distribution to the final consumer. There is usually a specialization of roles, and any single organization usually partidpares in the wider value system that creates a product or service. In understanding how value is created it is not enough to look at the firm's internal value chain alone. Much of rhe value creation will occur in the supply and distribution chains, and this whole process needs to be analysed and undersrocxl.

Suppliers have value chains that create and deliver the purchased inputs used in a firm's chain (the upstrea m parr of the value chain). Suppliers not only deliver a product, but can also influence a firm's performance in many orher ways. For example, Benetton, the Italian fashion company, managed to sustain an elaborate network of suppliers, agents and independent retail outlets as rhe basis of its rapid and successful internariond develop。 menr during the 1970s and 1980s.

In addition, products pass through the value chain channels on their way to rhe buyer. Channds perform additional acrivir ies thar affea the buyer and influence the firm's own activities. A firm's prThere are often circumstances where the overall cost can be reduced (or rhe value increased) by

Internationalizing the value chain

All internationally oriented firms must consider an evenrual internationaIizanon of rhe value chain's functions. The firm must decide whether rhe responsibility for the single value chain function is to be moved to the export markets or is best handled centrally from head office. Principally, the value chain function should be carried out where there is rhe highest competence (and the nx>st cost-effecciveness), and this is not necessarily ar head office.

A distinction immediately arises between the activities labelled downstream in Figure 1.11 and those labelled upstream activities. The location of downstream activities, those more related to the buyer, is usually tied to where the buyer is located. If a firm is going to sell in Australia, for example, it must usually provide services in Australia, and ir must have salespeople starioned there. In some industries it is possible ro have a singk sales force that cravds to rhe buyer's country and back again; other specific downstream activities, such as the production of advertising copy, can sometimes also be performed centrally. More typically, however, the firm must locate rhe capability ro perform downsrream activities in each of the countries in which it operates. By contrast, upstream activities and support activities are more independent of where rhe buyer is located (Figure 1.13). However, if the export markets are culturally dose to the home marker, it may be relevant to control rhe entire value chain from head office (home market).

This distinction carries some interesting implicarions. First, downstream activities create competitive advantages that are largely country-specific: a firm's reputation, brand name and service network in a country grow largely out of its activities and create entry/ mobility barriers largely in that country alone. Competitive advantage in upstream and support activities •often grows more our of the entire sy stem of countries in which a firm comperes than from its posirion in any single country.

Secondly, in industries where downstream acrivirics or other buyer-tied activities are viral to competitive advantage, there tends to be a more multidomestic pattern of inter national competition. In many service industries, for example, nor only downstream activi* ties but frequently upstream acrivicies are tied to buyer location, and global strategies are comparatively less common. In industries where upstream and support acrivities such as technology development and operarions are crucial to comperirive advantage, global competition is more common. For example, there may be a large need in firms to centralize and coordinate rhe producrion function worldwide to be able co create rational produc- tion units that are able to exploit economies of scale. Today it is very popular among companies to outsource production to the Far East, e.g. China.

Furthermore, as customers increasingly join regional cooperative buying organizations, it is becoming more and more difficult co sustain a price differentiation across markets. This will put pressure on the firm to coordinate a European price policy. This will be discussed further in Chapter 11.

The distinctive issues of international strategies, in contrast to domestic, can be summarized in two key dimensions of how a firm comperes internationally. The first is called the con fibration of a firm's worldwide activities, or the location in the world where each activity in the value chain is performed, including the number of places. For example, a company can locate different parts of its value chain in different places — for instance, factories in China, call centres in India and retail shops in Europe. IBM is an example of a company rhar exploits wage differentials by increasing the number of employees in India from 9,000 in 2004 co 50,000 by mid-2007 and by planning for massive additional growth. Most of these employees are in IBM Global Services, the part of rhe company that is growing fastest but has the lowest margins — which the Indian employees are supposed to improve, by reducing (wage) costs rather than raising prices (Ghemawac, 2007).

The second dimension is called coordination, which refers to how idenneal or linked acrivicies performed in different countries are coordinat-ed with each other (Porter, 1986).

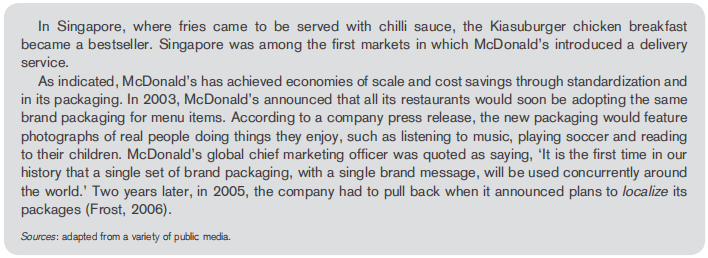

1.8 Value shop and the 1 service value chain'

Michael Porter's value chain model claims to identify the sequence of key generic activities rhar businesses perform in order to generate value for customers. Since its introduction in 1985, this model has dominated rhe thinkingof business executives. Yet a growing number of service businesses, including banks, hospitals, insurance companies, business consulting services and telecommunications companies, have found that the traditional value chain model does not fir the reality of their service industry sectors. Stabell and Fjeldstad (1998) identified rwc new models of value creation 一 value shops and value networks. Fjeldstad and Stabell argue that the value chain is a model for making products, while rhe value sh op is a model for solving customer or client problems in a service environment. The value network is a model for mediating exchanges between customers. Each model utilizes a different set of core activities to create and deliver distinct forms of value to customers.

The main differences between rhe two types of value chains are illustrated in Table 1.2.

Value shops (as in workshops, not retail stores) create value by mobilizing resources (e.g. people, knowledge and skills) and deploying them to solve specific problems such as curing an illness, delivering airline services to rhe passengers or delivering a solution co a business problem. Shops are organized around making and executing decisions — identifying and assessing problems or opportunities, developing alternative solutions or approaches, choosing one, executing it and evaluating the results. This model applies to most service-oriented organizations such as building contractors, consultancies and legal organizations. However, it also applies to organizations chat are primarily configured to identify and exploit specific marker opportunities, such as developing a new drug, drilling a potential oilfield or designing a new aircraft.

Different parrs of a typical business may exhibit characteristics of different configurations. For example, production and distribution may resemble a value chain; research and development a value shop.

Value shops make use of specialized knowledge-based systems to support the task of creating solutions to problems. However, the challenge is to provide an integrated set of applications that enabk seamless execution across rhe entire problem-soIving or opportunity—exploitation process. Several key technologies and applications are emerging in value shops — many focus on utilizing people and knowledge better. Groupware, intranets, desktop vi deoco nfere n ci ng and shared electronic workspaces enhance communication and collaboration between people, essential to mobilizing people and knowledge across value shops, integrating project planning with execution is proving crucial, for example, in pharmaceutical development, where bringing a new drug through rhe long, complex approval process a few months early can mean millions of dollars in revenue. Technologies such as inference engines and neural networks can help to make knowledge about problems and rhe process for solving them explicit and accessible.

The term 'value network' is widely used but imprecisely defined, k often refers to a group of companies, each specializing in one piece of the value chain, and linked together in some virtual way to create and deliver products and services. Srabell and Fjeisrad (1998) define value networks quire differently — nor as networks of afGlhted companies, bur as a business model for a single company that media res int€r actions and exchanges across a network of its customers. This model clearly applies best to tdecommunicarions companies, bur also ro insurance companies and banks, whose business, essentially, is mediating between cuscomers with different financial needs — some saving, some borrowing, for example. Key activities include operating the customer-connecring infrastructure, promoting rhe network, managing contracts and relationship丄 and providing services.

Some of the most IT-intensive businesses in the world are value networks — banks, airlines and telecommunications companies, for instance. Most of their technology pro vides rhe basic infrasrrucui re of the ’network' to media re exchanges between customers. Bur rhe competitive landscape is now shifting beyond au co mat ion and efficient transaction processing to monitoring and exploiting information about customer behaviour.

The aim is to add more value to customer exchanges through better understanding of usage panerns, exchange opportunities, shared interests and so on. Data mining and visualization tools, for example, can be used ro identify both positive and negative connections between customers.

Compecirive success often depends on more than simply performing your primary model well. It may also require the delivery of additional kinds of complementary value. Adopting anributcs of a second value configuration model can be a powerful way to differentiate your value proposition or defend ir against competitors pursuing a value model different ro your own. 1c is essential, however, to pursue another model only in ways that leverage the primary model. For example, Harley-Davidson's primary model is rhe chain— it makes and sells prtxlucrs. Forming the Hurley Owners Group (HOG) — a network of customers — added value to the primary model by reinforcing the brand identity, building loyalty and providing valuable information and feedback about customers' behaviours and preferences. Amazon.com is a value chain like other book distributors, and initially used technology ro make rhe process vastly more efficient Now, with irs book recommendations and special interest groups, it is adding the characteristics of a value nework. Our research suggests that the value network, in particular, offers opportunities for many existing businesses to add more value ro rheir customers, and for new entrants ro capture market share from those who offer less value to their customers.

Combining the product value chain and the service value chain

Blomstermo et al. (2006) make a distinction between hard and soft services. Hard services are those where prcxlucrion and consumption can be decoupled. For example, software services can be transferred into a CD or some other tangible medium, which can be mass-produced, making standardizarion possible. With soft services, where production and consumption occur simultaneously, rhe customer acts as a co-producer, and decoupling is nor viable. The soft-service provider must be present abroad from its first day of foreign operations.

Figure 1.14, showing the combination of rhe product and service value chains, is mainly valid for soft services, but at the same time in more and more industries we see that physical prod* nets and services are combined.

Most product companies offer services to protect or enhance the value of rheir product businesses. Cisco, for instance, built its installation, maintenance and network-design service business to ensure high-quality product support and to strengthen relationships with enterprise and telecom customers. A company may also find itself drawn into services when it realizes that competitors use its products to offer services of value. If it does nothing, it risks nor only rhe commoditization of its own products — something that is occurring in mosr product markets, irrespective of rhe services on offer - bur also the loss of customer relat ionships. To make existing service groups profitable — or to succeed in launching a new embedded service business 一 executives of product companies must decide whether the primary focus of service units should be co support existing produce businesses or to grow as a new and independent platform.

When a company chooses a business design for delivering embedded services to customers, it should remember that its strategic intent affects which ekments of rhe delivery life cyde are most important. If the aim is ro protect or enhance the value of a product, the company shouId integrate the system for delivering it and rhe associated services in order co promote rhe devdopment of product designs that simplify the task of service (e.g. by using fewer subsystems or integrating diagnostic software). This approach involves minimizing the footprint of service delivery and incorporating support into the product whenever possible. If the company wants rhe service business to be an independent growth platform, however, it should focus most of its delivery efforts on constantly reducing unit costs and making the services more productive (Auguste et al.t 2006).

In the "moment of truth" (e.g. in a consultancy service situation), rhe seller represents all rhe functions of the focal company's product and service value chain — at the same time. The seller (the product and service provider) and the buyer create a service in an interaction process: 'The service is being created and consumed as it is produced/ Good representatives on rhe seller's side are vital co service brands' successes, being ultimately responsible for delivering the seller's promise. As such, a shared understanding of rhe service brand's values needs ro be anchored in their hearts and minds ro encourage brandsupporting behaviour. This internal brand-building process becomes more challenging as service brands expand internarionally, drawing on workers trom different global domains.

Figure 1.14 also shows the cyclic nature of rhe service inreraction ('moment of truth') where the post-evaluarion of rhe service value chain gives input for rhe possible redesign of the'product value chain'. The inreraction shown in Figure 1.14could also bean illustration or a snapshot of a negotiation process between sailer and buyer, where the seller represents a branded company, which is selling its projects as a combination of 'hardware' (physical products) and 'software' (services).

One of rhe purposes of the 'learning nature' of rhe overall decision cyde in Figure 1.14 is to pick up rhe best practices among different kinds of international buyer—seller interactions. This would lead ro a better set-up of:

- the service value chain (value shop);

- the product value chain;

- the combination of the service and product value chain.

Johansson and Jonsson (2012) emphasized the knowledge transfer between rhe producc value chain and rhe value shop, by looking at value creation and utilizing the synergies between them. This is especially relevant to consider in business ro business (B2B) project selling.

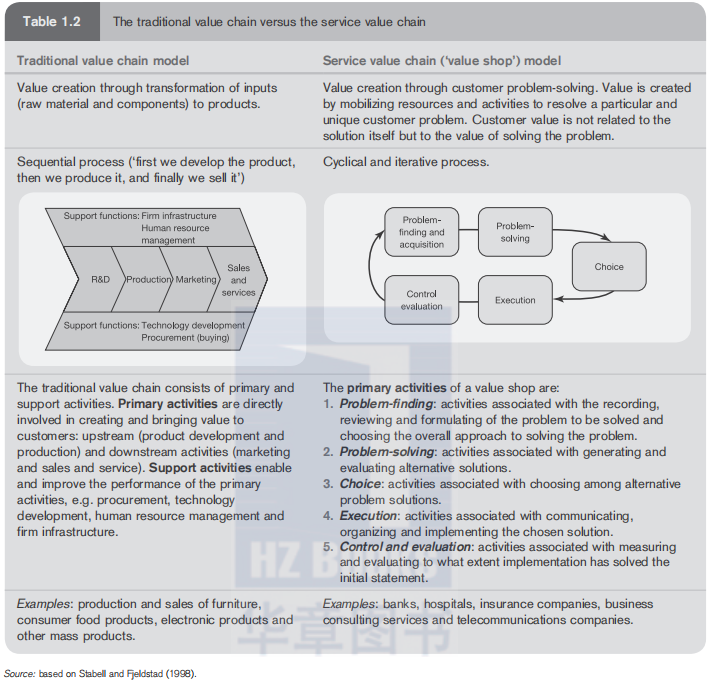

1.9 Global experimental marketing

The previous section describes and explains value creation as a resuk of both the product and service offerings. However, as services increasingly become commcxliuzed—think of smartphone services sold solely on price—'experiences' have emerged as the next step in providing 'customer value'. This process of generating customer value from a product solution, services and finally customer experiences is shown in Figure 1.15. A customer experience occurs when a company intentionally uses products in combination with ser- individual customers in a way that creates a memorable event (Pine andvices to engage Gilmore, 1998).

Experiential marketing is a growing trend worldwide, evident in most sectors of rhe global economy. The term essentially describes marketing initiatives that give customers in-depth, tangible experiences in order to provide them with sufficient information to make a purchasing decision. It has evolved as a response ro a perceived transirion from a service economy to one personified by the experiences in which consumers parricipate.

Unless companies want to be in a commoditized business, they will be compelled to upgrade their offerings to rhe nexc stag^ of customer value creation: customer experience. This applies ro both B2C (business ro consumer) and B2B businesses.

B2C businesses

It is increasingly the case that consumers are involved in the processes of both defining and creating value, and the co-created experience of consumers through rhe holistic brand value strucru re becomes rhe very basis of marketing.

Pine and Gilmore (1998) suggest chat we think about experiences across two bi-polar constructs:

- Involvement/participation. This dimension refers to rhe level of interactivity between rhe supplier and the customer. At 'low degree* there is passive parucipation, where the participants experience the event as observers or listeners, e.g. classical symphonygoers. At the other end of rhe spectrum lies 'active paniciparion' in which customers play key roles in creating rhe performance or event, e.g. going to a rock concert.

- Intensity/connection. This dimension refers to the strength of feding towards the interaction. Watching a film in the cinema (e.g. an IMAX theatre) with an audience, 3D screen and advanced sound is associated with a 'high degree' of intensity/connection compared with watching rhe same film at home on a DVD.

We can sort experiences into four broad categories according co where they fall along rhe spectra of the two dimensions:

Entertainment

Entertainment can be defined as something that amuses, pleases or diverts (especially a performance or show), or is the pleasure afforded by beingentefuined and Amused. For example, fashion shows in designer boutiques and upmarket department stores, involving a low degree of customer involvement and intensity, would qualify as 'entertainment'.

Educational

Activities in the educational zone involve chose in which participants are more actively involved, bur the level of intensity is srill low. In this zone, participants acquire new skills or increase those they already have. Many company offerings include educational dimensions. For example, cruise ships often employ wdl-known authorities to provide semi- formal lectures as part of their itineraries, a concept commonly referred to as 'edutainment', Likewise, the Ferrari Driving Experience is a two-day precision driving school designed to narrow rhe gap between driving ability and a Ferrari's performance capability (Atwal and Williams, 2009).

This type of experience typically involves active participation by the consumer in educational activities of a srimularing nature, thus ensu ring that rhe event provides an experience.

Aesthetic

When the element of acrivity is reduced to a more passive involvement, the event becomes aesthetic. Admiring the architectural or interior design of designer boutiques, for example, involves high degree of intensity bur it has little effect on its environment.

In chiscategonr customers are involved in very incense experiences (e.g. a tourist viewing the Grand Canyon from its rim), but they are not personally involved in the event (such as climbing down the Grand Canyon as they might in the escapism category). Luxury brand acrivity is of an aesthetic nature, with customers immersing themselves in the experience but with lirtle active participation. Watching a Cirque du Solei! show (see cose 7.1) is a customer experience of this kind.

Escapism

Escapism can be defined as a tendency toescape from daily realities or routines by indulging in daydreams, fantasies or entertainment that provide a break from reality. Escapist activities are those char involve a high degree of both involvement and intensity, and are clearly a central tearure of much of luxury consumption and lifestyle experiences, often connected co rhe fitness trend. This is clearly evident in the luxury tourism and hospitality sector, with rhe growth of specialized holiday offerings, in which customers are closely involved in co-crearing cheir experiences. Joining a Zumba dance course (see case 3.1) is similar to this kind of customer experience.

B2B businesses

Like B2C companies, B2B businesses also need to cont in uously innovate how they attract, engage and excite customers by finding new possibilities for creating value. Leading industrial equipment suppliers, for instance, are learning that creation of customer value needs to be based on how customers experience the job they need to do now or how they prepare ro transform themselves to succeed in rhe future.

Mass customization

One of the best ways to create customer value is to engag,e customers and create experience by mass customizing goods and services for thetn. One of rhe benefits of digital technology is that B2B companies can mass customize offerings, efficiently serving customers uniquely, differentiating offerings from any competition, and locking customers in. This is because mass customizing a product automatically turns ir into a service. An integrated part of the mass customization process is the intangible service of helping customers figure out exactly what it is they want. So when B2B companies mass customize a product, they compete in the service business of helping their individual business customers define rheir needs, and then make and deliver customized products to meet rhoj^e needs for each of their customers.

Furthermore, mass customizing a service turns it into an experience because, when businesses design a custom service that is just right for a particular customer at a particular point in time, rhe result is an inherently personal, and memorable, interaction.

More and more customers seek out suppliers rh ar want to become partners in their customers, success, that help customers hdp their customers and that rhink beyond the value of the equipment they sell to the far greater value that accrues from helping customers use that equipment effectively. B2B businesses need to realize that customers don't really want just products, systems or even solutions. They want a better business. Customers that are growing and adapting to their markets do not just buy industrial equipment rod ay Because they want rhe equipment; ir is always a means to create a better and more profitable business. The ‘Case Construccion' exhibit (Exhibit 1.7) illustrates this point.

Augmented Reality (AR)

The way in which Augmented Reality (AR) has been used in marketing campaigns can be seen as a form of experiential marketing because it focuses nor only on a single product/ service, but also on an entire experience created for rhe customers. The technology enhances rhe customer's current perceprion of reality. By contrast, virtual reality replaces the real world with a simulated one. With the help of advanced AR, information about the surrounding real world of the user becomes interactive and digitally manipulable.

Experiential marketing is recognized as an important means of creating value for the end consumer, who will be motivated co make faster and more positive purchasing decisions. Consequently AR experiential marketing is considered as mainly affecting the prepurchase stage due to rhe fact that AR has the most impact ar the pre-purchase stage. At this stage the consumer is evaluating their choices before taking rhe final purchase decision and AR has rhe power to 'pur rhe product in the hand of the users' giving them the opportunity to test the product as if they already own it. Funhermore, AR has the potential to provide customers with an experience they appreciate and that they will tell their friends about.

In conclusion, whereas tradirional marketing frameworks view consumers as rational decision-makers focused on the functional features and benefits of products, experiential markering views consumers as emotional beings, focused on achieving memorable experiences. In this connexion the use of new technologies, such as social media, has also increased rhe potential for experiential marketing. This is of particular relevance given rhe increasing significance of the internet as a communication and discribudon channel within the luxury sector.

Finally, rhe more a company engages all five senses in rhe creation of a aistomer experience, rhe more effective and memorable it can be.

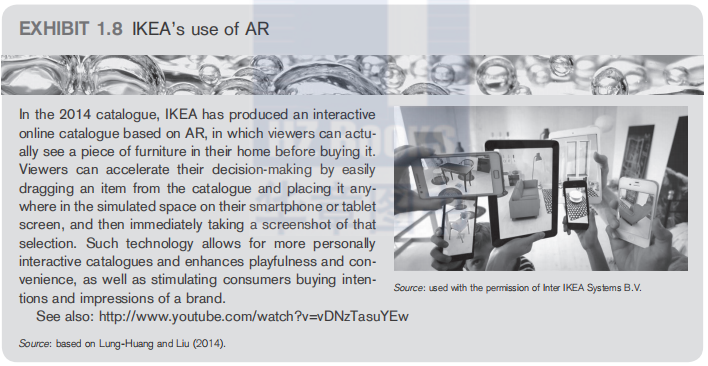

1.10Information business and the virtual value chain

Most business managers would agree that we have recently entered a new era, 'the information age', which differs markedly from rhe industrial age. What have been the driving forces for these changes?

The consensus has shifted over rime. To begin with, it was thought to be the automation power of computers and compucanon; then it was the ability to collapse time and space through relecommunicadons. More recently ir has been seen as rhe value-creating power of information, a resource that can be reused, shared, distributed or exchanged without any inevitable loss of value; indeed, value is sometimes mukiplied. Today's fasci- nanon with compering on invisible assets means that people now see knowledge and its relationship with inrellecrual capital as rhe critical resource, because it underpins innovation and renewal.

One way of understanding rhe strategic oppo rm nicies and threats of information is to consider the virtual value chain as a supplement to rhe physical value chain (Figure 1.16).

By introducing rhe virtual value chain, Rayport and Sviokla (1996) have made an extension to the conventional value chain model, which treats informa non as a supporting element in rhe value-adding process. Rayport and Sviokla (1996) show how information in itself can be to create value.

Fundamentally, there are four ways of using information co create business value (Marchand, 1999):

- ALukigiHg risks. In the rwenticih century the evolution of risk management stimulated the growth of functions and professions such as finance, accounting, auditing and controlling. These in formation-intensive functions rend to be major consumers of IT resources and people's rime.

- Reducing costs. Here the focus is on using information as efficiently as possible to achieve rhe outputs required from business processes and transactions. This process view of information management is closely linked with the re-engineering and continuous improvement movements of rhe 1990s. The common elements are focused on eliminating unnecessary and wasteful steps and activities, especially paperwork and informarion movements, and then simplifying and, if possible, automating rhe remaining processes.

- Offering products and services. Here the focus is on knowing one's customers, and sharing informarion with partners and suppliers to enhance customer satisfaction. Many service and manufacturing companies focus on building relationships with ais- romers and on demand management as ways of using information. Such strategies have led companies ro invest in point-of-sale systems, account management, customer profiling and service management systems.

- Inventing new products. Finally, companies can use information to innovate — ro invent new products, provide different services and use emerging technologies. Companies such as Inrd and Microsoft are learning co operate in 'continuous discovery mode' inventing new products more quickly and using market intelligence to retain a competitive edge. Here, information management is about mobilizing people and collaborative work processes to share informarion and promote discovery throughout rhe company.

Every company pursues some combination of rhe above strategies.

In relation ro Figure 1.16, each of the physical value chain activities might make use of one or all four i nto rm ar io n-p rocessi ng stages of the virtual value chain, in order to create extra value for rhe customer. This is rhe reason for the horizontal double arrows between rhe different physical and virtual value chain activities in rhe figure. In this way informarion can be captured at all stages of the physical value chain. Obviously such information can be used to improve performance ar each stage of the physical value chain and to coordinate elements across ir. However, it can also be analysed and repackaged to build content-based products or co create new lines of businesses.

A company can use its information to reach out to other companies' customers or operations, thereby rearranging the value system of an industry. The result might be that tradirional industry sector boundaries disappear. The CEO of Amazon.com, Jeff Bezos, clearly sees his company as being not in rhe book-selling business but in the informationbroker business.

1.11 Summary

Porter's original value chain model was introduced as a framework model for major parts of this book. In understanding how value is created, it is not enough to look at the firm's internal value chain alone. In most cases the supply and distribution value chains are interconnected, and this whole process needs to be analysed and understood before considering an eventual internationalization of value chain activities. This also involves decisions about configuration and coordination of the worldwide value chain activities.

As a supplement to rhe rraditional (Porter) value chain, the service value chain (based on rhe so-called fcvalue shop' concept) has been introduced. Value shops create value by mobilizing resources (people, knowkdge and skills) and deploying them to solve specific problems. Value shops are organized around making and executing decisions in the specific service interaction simation with a customer — identifying and assessing service problems or opportunities, developing akernarive solutions or approaches, choosing one, executing it and evaluating the results. This model applies to most service-oriented organizations.

Many product companies want to succeed with embedded services: as competirive pressures increasingly commoditize product markers, services will become the main differentiator of ualue creation in coming years. However, companies will need a clearer understanding of rhe strategic rules of this new game — and will have to integrate rhe rules into their operations — to realize the promise of these fasr-growing businesses.

Today, rhe right combination of the product value chain and the service value chain is nor a sufficient competitive differentiator. Adding ^customer experiences' occurs when a company inretitionally uses products in combination with services, to engage individual customers in a way that creates a memorable event that can be characterized in one of four groups: enrerr;iinment9 educational, aesthetic or escapist.

Ac the end of rhe chapter the virtual value chain was introduced as a supplement to rhe physical value chain, thus using information to create further business value.

Questions for discussion

1.What is the reason for the Convergence of onentarion, in LSEs and SMEs?

2.How can an SME compensate for its lack of resources and expertise in global marketing when trying to enter export markets?

3.What are the main differences between global marketing and markering in the domestic context?

4.Explain the main advantages of centralizing upstream activities and decentralizing downstream activities.

5.Explain how a combination of the product value chain and the service value chain can create funher customer value.

6.How is the virtual value chain different from rhe conventional value chain?

References

Asugman, G., Johnson, J.L. and McCullough, J. (1997) ‘The role of after-sales service in interna?tional marketing’, Journal of International Marketing, 5(4), pp. 11–28.

Atwal, G. and Williams, A. (2009) ‘Luxury brand marketing – the experience is everything’, Brand Management, 16(5/6), pp. 338–346.

Auguste, B.G., Harmon, E.P. and Pandit, V. (2006) ‘The right service strategies for product compa?nies’, McKinsey Quarterly, 1 March, pp. 10–15.

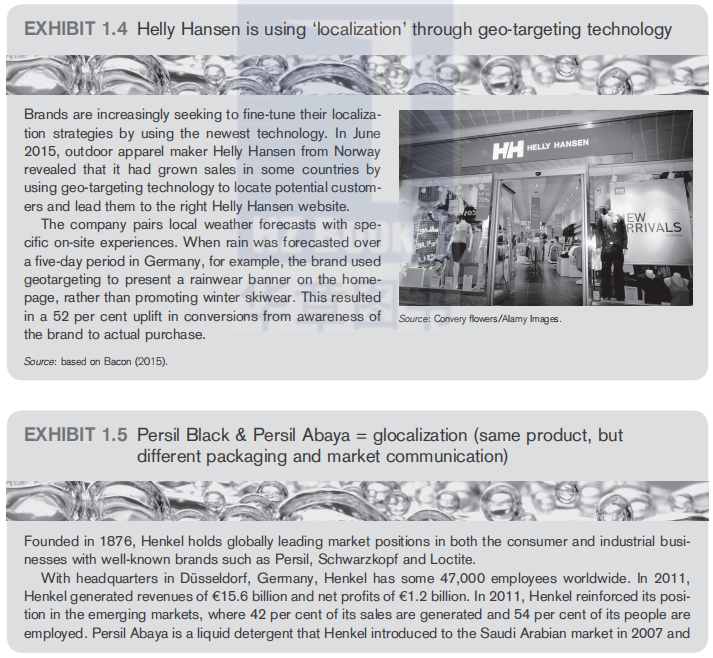

Bacon, J. (2015) ‘How to avoid your message getting lost in translation’, Marketing Week, 18 June, pp. 23–25.

Bailey, C.K., Knepler, B., and Vaanlombeek, P. (2015) ‘Creating flexible global brnads in federated organisations: A case study from a global not-for-profit’, Journal of Brand Strategy, 3(4), pp. 350–356.

Beinhocker, E., Davis, I. and Mendonca, L. (2009) ‘10 trends you have to watch’, Harvard Business Review, July–August 2009, pp. 55–60.

Bellin, J.B. and Pham, C.T. (2007) ‘Global expansion: balancing a uniform performance culture with local conditions’, Strategy & Leadership, 35(6), pp. 44–50.